Soil classification at Kaiser-Wilhelm-Koog

25 January 2022, by RTG2530

Photo: UHH/GRK2530/Neiske

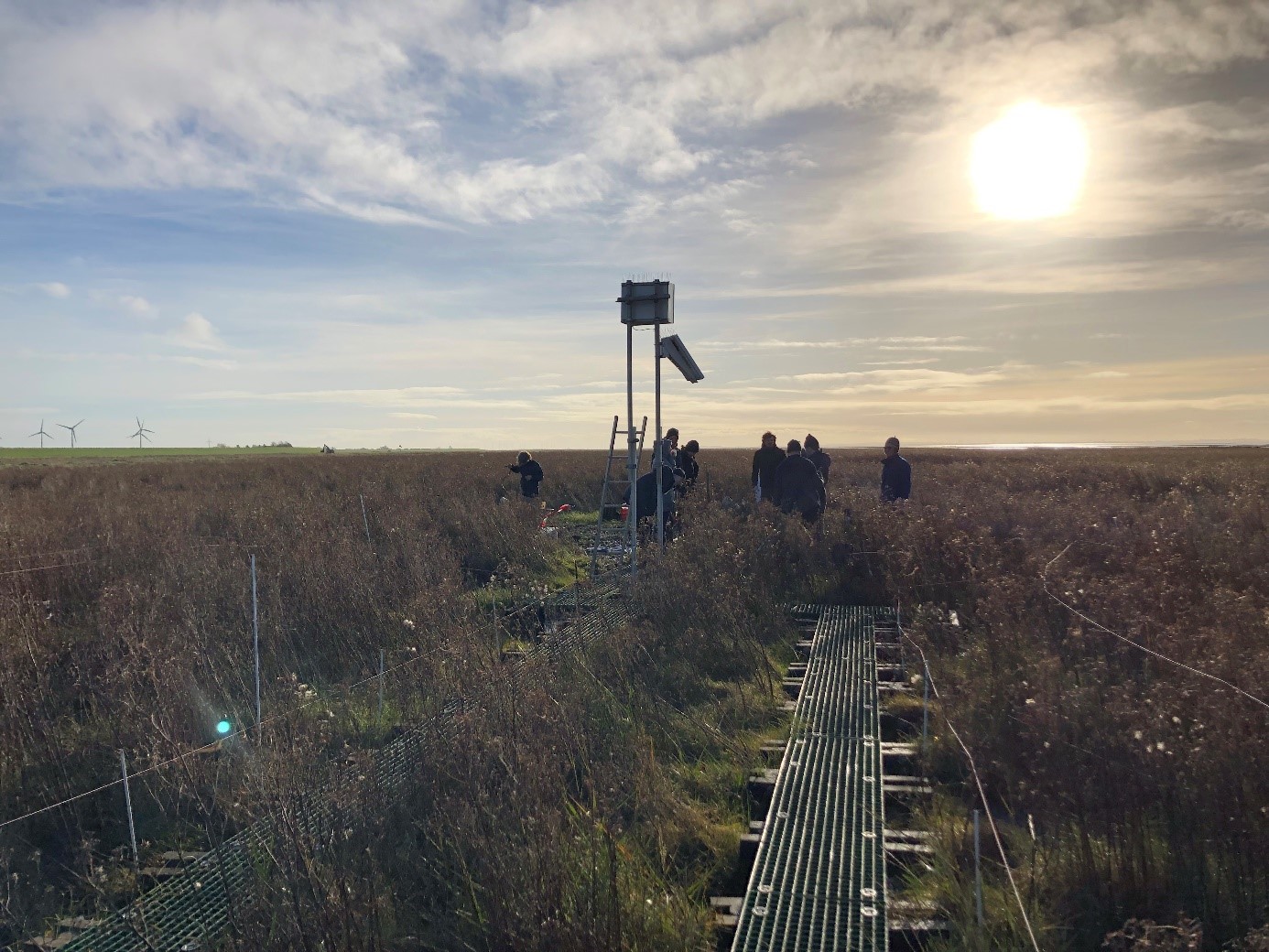

Researchers from Research Training Group 2530 headed to the research station at Kaiser-Wilhelm-Koog in November 2021 to conduct soil classifications, place sensors in the ground and collect samples.

The sun hasn’t fully risen as ten people wade through the muddy substrate along the Elbe River with shovels, blue tarps and rubber boots. They have come to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Koog to dig several holes in the ground of the marsh - and later fill them in again.

What seems like the opening of a crime story is actually important preliminary work for the research conducted by Research Training Group 2530. Over the course of two days, the researchers classified soils, placed sensors in the ground and took samples around the research site at Kaiser-Wilhelm-Koog.

"Soil classification means we'll be studying what kind of soil is in the marsh," explains Fay Lexmond, a doctoral student in the graduate program. To do this, the researchers dig a two-by-two-meter wide and 60 centimeter deep hole in the ground, which is usually referred to as “soil pit”, take several photographs and various soil samples back to the laboratory. "By using an international manual, the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB), you can then determine what soil types are at that location. It works similar to plant determinations, where the plants are matched to the manual", says Lexmond. The collected samples are also taken back to the lab and stored in a fridge or freezer. They can then be studied in more detail for example with regard to nutrient and carbon contents.

The soil classification will be useful for all doctoral students collecting data at the research site. "In the RTG we want to study the influence of biota - this means plants, animals and microorganisms - on the carbon cycle in estuaries. And soil properties have a crucial influence on ecosystem processes, such as plant growth," says Fay Lexmond. "If we know the soil types, it gives us an indication of what to expect."

What sounds simple in theory is hard work: in the end, it took the ten researchers two days to dig the four holes. The muddy ground and environmental conditions made the work difficult. The closer the team got to the banks of the Elbe, the faster the hole filled with water from the ground. "In one hole, the water even rose so quickly that I couldn’t collect all the soil samples at once. We had to alternate taking a sample, then emptying the pit again and then I could take another sample before having again to empty the soil pit," says Lexmond.

Before filling the holes back in, the team left two types of sensors in them, which provides scientists with data on temperature and moisture in the soil over the coming years. "This data will also provide important information that will help us answer our research questions," says Fay Lexmond.